22 October 2011

The Manis Mastodon

Addendum: Adding to the Manis Mastodon's Northwest cred, Knute Berger, my favorite Seattle journalist has supplied a brief article on the subject.

13 October 2011

Fossil Vertebrate of the Month - Terror Bird

07 September 2011

Fossil Vertebrate of the Month: Megalonyx jeffersoni

09 May 2011

Orcutt & Hopkins, 2011

02 May 2011

Fossil Vertebrate of the Month: Archaeotherium

19 April 2011

Fun With Body Mass Estimates

02 April 2011

Fossil Vertebrate of the Month: Baryonyx walkeri

06 March 2011

José María Velasco

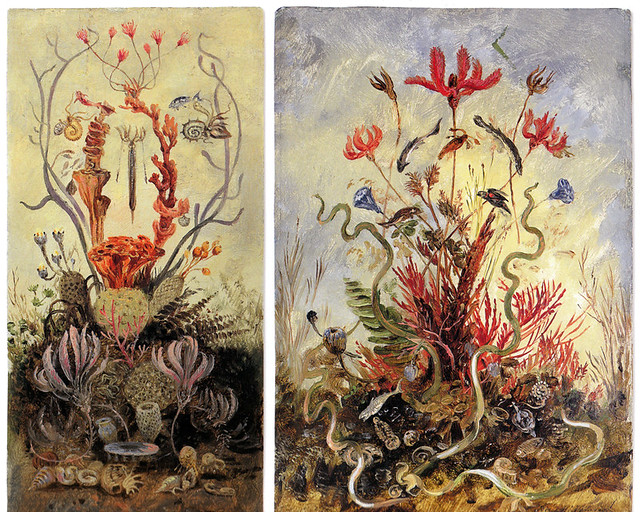

The paintings above, as well as a third of cave bears that I couldn't find an imagine for online, are by the artist José María Velasco, who I have to admit I'd never heard of before my trip. He lived and worked in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries and is best remembered for his landscapes of the Valley of Mexico, which have served as a touchstone of Mexican national identity. He was also a scientist, with a particular interest in natural history (a running theme in his profession, it so transpires, as Mexico's greatest landscape artist, Dr. Atl, was also an amateur volcanologist and advocate for science); he even described a species of salamander, that has since been renamed in his honor. This may explain why he was commissioned to decorate UNAM's Instituto de Geologia. Velasco's paintings have adorned the palatial building (itself as glorious an example of early 20th Century museum architecture and design as you'll find anywhere in the world) near central Mexico City since the 1910s, and had been brought over to the UNAM exhibit during some renovations (you can get a sense of how they look in situ in this picture). Information on the paintings is scarce, but it appears that Velasco painted two series: one tracing the history of marine life and one depicting terrestrial animals and landscapes through time. These would have been painted at roughly the same time as some of the greatest works of Charles R. Knight and his European counterpart, Heinrich Harder, and I would argue that not only are Velasco's reconstructions in the same league as those of his more famous contemporaries (though it must be said that no one before or since can compete with the vibrancy of Knight's animals), but he in fact surpasses them in many ways; his paleo-landscapes are especially impressive (though sadly underrepresented online). This should come as no surprise, as Velasco was, after all, a classically trained painter and one of his country's greatest artists of the pre-modern era. It seems a shame that his contributions to scientific illustration and paleoart should have lapsed into obscurity, and I thought I'd do my humble best to try to share some of those contributions with the world.

02 March 2011

Brontomerus, Hell Creek, and Mesozoic Ecology

01 March 2011

Fossil Vertebrate of the Month: Megaloceros giganteus

21 February 2011

Oregon Trail Word Cloud

01 February 2011

Humboldt, Bergmann, and Haeckel: The German Roots of Ecology

The authors of these three papers no doubt had many things in common, but perhaps the most striking is that they shared a country of origin. At first glance, it seems illogical that ecology should have been born in Germany (which, after all, was only a collection of smaller kingdoms and principalities until 1871). Germany has always produced great scientists, from Leibniz to Einstein, but in Humboldt's time Paris was the center of the scientific world, and many of the most celebrated accomplishments of 19th Century science took place not on the Continent but across the English Channel. Even within biology, France and Britain played a dominant role, producing some of the greatest anatomists and, later, evolutionary biologists that have ever lived. Nonetheless, ecology was, at its root, a uniquely German phenomenon. This begs a rather obvious question: why? While I'm a far better paleontologist than historian, I think think I have the glimmer of an answer, but in the interest of keeping unassailable historical facts apart from more baseless arm-waving, I'll save my thoughts for a later post. Stay tuned...

Fossil Vertebrate of the Month: Megatherium americanum

10 November 2010

Fossil Vertebrate of the Month: Diplodocus carnegii

Last month's Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meeting was held in Pittsburgh and while animal chosen for the conference logo was the awkwardly-named tetrapod Fedexia, there is another animal that will forever be associated with vertebrate paleontology in that city's Carnegie Museum of Natural History. The museum has existed since 1895, but it was in 1898 that its namesake would spur the discovery of its most famous specimen. It's unclear whether Andrew Carnegie was alerted to the publicity value of sauropod skeletons by a visit to the American Museum of Natural History or by a sensational newspaper headline trumpeting the discovery of "The Most Colossal Animal Ever On Earth." Regardless of the cause, he hired away some of the AMNH's paleontologists and sent them to the badlands of Wyoming to find a giant dinosaur for his museum. His team succeeded spectacularly, and in 1901 the fruits of their labor were described as Diplodocus carnegii. The skeleton, which for decades was the longest - though far from largest - dinosaur known, was a huge hit in Pittsburgh and around the world, as Carnegie presented casts of the skeleton (known affectionately as Dippy) as gifts to museums in capitals across the globe. Dippy even has a couple of connections to paleontology in Oregon: D. carnegii was one of the taxa modeled by UO computer scientist/paleontologist Kent Stevens, and the cast presented by Carnegie to London's Natural History Museum was the first fossil I ever saw and was largely responsible for setting me down the path I'm still traveling today.

Last month's Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meeting was held in Pittsburgh and while animal chosen for the conference logo was the awkwardly-named tetrapod Fedexia, there is another animal that will forever be associated with vertebrate paleontology in that city's Carnegie Museum of Natural History. The museum has existed since 1895, but it was in 1898 that its namesake would spur the discovery of its most famous specimen. It's unclear whether Andrew Carnegie was alerted to the publicity value of sauropod skeletons by a visit to the American Museum of Natural History or by a sensational newspaper headline trumpeting the discovery of "The Most Colossal Animal Ever On Earth." Regardless of the cause, he hired away some of the AMNH's paleontologists and sent them to the badlands of Wyoming to find a giant dinosaur for his museum. His team succeeded spectacularly, and in 1901 the fruits of their labor were described as Diplodocus carnegii. The skeleton, which for decades was the longest - though far from largest - dinosaur known, was a huge hit in Pittsburgh and around the world, as Carnegie presented casts of the skeleton (known affectionately as Dippy) as gifts to museums in capitals across the globe. Dippy even has a couple of connections to paleontology in Oregon: D. carnegii was one of the taxa modeled by UO computer scientist/paleontologist Kent Stevens, and the cast presented by Carnegie to London's Natural History Museum was the first fossil I ever saw and was largely responsible for setting me down the path I'm still traveling today.

18 September 2010

Research Report: Mexico City

Whenever I tell anyone that I'm a paleontology student, one of the questions I inevitably get is 'Where do you do your field work?' When I tell them that I don't really do field work and that I do my research in the basements of museums, they usually say something to the effect of 'Oh, that's too bad.' Actually, it isn't. For one thing, the best science in our field is done indoors in collections, libraries, and labs. For another, I actually enjoy collections work (you can see a lot more fossils in a day in a museum than you ever will in the field). For yet another, it can take you to some of the best parts of the world. So far my collections visits have brought me home to Seattle, across the Cascades to John Day, to the great cities of California, to the university towns of the Rockies and Great Plains, to New York's unsurpassed temple to natural history, and now they've brought me to one of the greatest, most historic, and culturally rich cities on the planet. I'm writing this post from Coyoacan, a colonial town turned urban neighborhood in Mexico City. I've come to visit the collections of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México in order to expand the scope of my dissertation to all of North America rather than just the US. While I've made an avowed effort to cut down on travelogue-type entries on this blog, this is the first international research trip I've taken, and as such a few posts from south of the border might be of more general interest than the usual "this is what I did today and this is what I think of it" travel update. I'll do my best to supply a few of these posts on the state of my research and of paleontology and science in Mexico during the duration of my visit this week, so stay tuned.

Whenever I tell anyone that I'm a paleontology student, one of the questions I inevitably get is 'Where do you do your field work?' When I tell them that I don't really do field work and that I do my research in the basements of museums, they usually say something to the effect of 'Oh, that's too bad.' Actually, it isn't. For one thing, the best science in our field is done indoors in collections, libraries, and labs. For another, I actually enjoy collections work (you can see a lot more fossils in a day in a museum than you ever will in the field). For yet another, it can take you to some of the best parts of the world. So far my collections visits have brought me home to Seattle, across the Cascades to John Day, to the great cities of California, to the university towns of the Rockies and Great Plains, to New York's unsurpassed temple to natural history, and now they've brought me to one of the greatest, most historic, and culturally rich cities on the planet. I'm writing this post from Coyoacan, a colonial town turned urban neighborhood in Mexico City. I've come to visit the collections of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México in order to expand the scope of my dissertation to all of North America rather than just the US. While I've made an avowed effort to cut down on travelogue-type entries on this blog, this is the first international research trip I've taken, and as such a few posts from south of the border might be of more general interest than the usual "this is what I did today and this is what I think of it" travel update. I'll do my best to supply a few of these posts on the state of my research and of paleontology and science in Mexico during the duration of my visit this week, so stay tuned.

06 September 2010

Fossil Vertebrate of the Month: Epicyon haydeni

Last month, while measuring teeth in the collections of the University of Montana and Idaho State University, I came across jaws of one of the more impressive carnivores ever to have lived. The picture at left (from UM) may not do the size of the animal justice, but Epicyon haydeni is the most massive known canid; the largest known individuals may have exceeded 200 pounds, putting them well within the size range of modern black bears. Epicyon was a member of a group of canids known as borophagines that were among the most common carnivores of the North American Oligo-Miocene. Borophagines are often described as hyena-like, and many of the larger taxa - including Epicyon - were likely bone-crushing predators. However, the group was very diverse and many of its members, especially in the Oligocene and Early-Mid Miocene, were actually fairly small; at least one species had an almost raccoon-like morphology. In many Late Miocene faunas, two species of Epicyon co-occur: the larger E. haydeni and the smaller (but still very big) E. saevus. Canid experts extraordinaire Xiaoming Wang and Richard Tedford have suggested that this is the result of character displacement, making Epicyon an excellent example of how the fossil record can record ecological and evolutionary patterns.

Last month, while measuring teeth in the collections of the University of Montana and Idaho State University, I came across jaws of one of the more impressive carnivores ever to have lived. The picture at left (from UM) may not do the size of the animal justice, but Epicyon haydeni is the most massive known canid; the largest known individuals may have exceeded 200 pounds, putting them well within the size range of modern black bears. Epicyon was a member of a group of canids known as borophagines that were among the most common carnivores of the North American Oligo-Miocene. Borophagines are often described as hyena-like, and many of the larger taxa - including Epicyon - were likely bone-crushing predators. However, the group was very diverse and many of its members, especially in the Oligocene and Early-Mid Miocene, were actually fairly small; at least one species had an almost raccoon-like morphology. In many Late Miocene faunas, two species of Epicyon co-occur: the larger E. haydeni and the smaller (but still very big) E. saevus. Canid experts extraordinaire Xiaoming Wang and Richard Tedford have suggested that this is the result of character displacement, making Epicyon an excellent example of how the fossil record can record ecological and evolutionary patterns.

31 July 2010

Fossil Vertebrate of the Month: Oncorchynchus rastrosus

Salmon are a symbol of the Northwest, and with good reason: not only have they been a staple food for humans for millennia and a hugely important link in regional food chains for much longer, but they have very deep roots here. Go back to the Late Miocene and you would still see salmon in the rivers of Oregon; you would, in fact, see one of the most impressive prehistoric fish ever discovered: Oncorhynchus rastrosus, the sabertooth salmon. The features that gave the fish its common name (and its original genus name, Smilodonichthys) are its enlarged canines which, arresting as they are, are not as unusual as they might seem, as many modern salmon grow large breeding teeth while migrating upstream to spawn. The size of O. rastrosus, though, is unique: at lengths of up to 2 meters, it was a good deal larger than the largest known Chinook salmon and head and shoulders beyond sockeyes, its nearest living relatives. The sabertooth salmon was in the news this last month (both in the paper and on TV) after a team led by the University of Oregon's own Edward Davis performed a CAT-scan on its skull. The result of this research is a series of impressive 3-D reconstructions, which can be viewed in an online exhibit by the U of O Museum of Natural & Cultural History; if you'd rather see the original in person, it will be part of the museum's revamped PaleoLab exhibit opening this month.

Salmon are a symbol of the Northwest, and with good reason: not only have they been a staple food for humans for millennia and a hugely important link in regional food chains for much longer, but they have very deep roots here. Go back to the Late Miocene and you would still see salmon in the rivers of Oregon; you would, in fact, see one of the most impressive prehistoric fish ever discovered: Oncorhynchus rastrosus, the sabertooth salmon. The features that gave the fish its common name (and its original genus name, Smilodonichthys) are its enlarged canines which, arresting as they are, are not as unusual as they might seem, as many modern salmon grow large breeding teeth while migrating upstream to spawn. The size of O. rastrosus, though, is unique: at lengths of up to 2 meters, it was a good deal larger than the largest known Chinook salmon and head and shoulders beyond sockeyes, its nearest living relatives. The sabertooth salmon was in the news this last month (both in the paper and on TV) after a team led by the University of Oregon's own Edward Davis performed a CAT-scan on its skull. The result of this research is a series of impressive 3-D reconstructions, which can be viewed in an online exhibit by the U of O Museum of Natural & Cultural History; if you'd rather see the original in person, it will be part of the museum's revamped PaleoLab exhibit opening this month.

Field Report: Field Camp 2010

As many of you may know, I was the TA for the paleontology portion of the U of O's field camp this year. Since I got back earlier this week, several people have asked me what we did and what we found. I may not be a great blogger, but even I know the first rule of journalism, so in the interest of giving the people what they want, here's a brief summary of what went on (You'll notice that I'm not giving names or locations of any of the work we did; we were at two sites, both of which are publicly owned, and since illegal collection on federal land is a recurring problem in eastern Oregon, I don't want to provide any information that an unscrupulous fossil poacher might be able to use; for those of you who are wondering, yes, we did have the appropriate permits).

As many of you may know, I was the TA for the paleontology portion of the U of O's field camp this year. Since I got back earlier this week, several people have asked me what we did and what we found. I may not be a great blogger, but even I know the first rule of journalism, so in the interest of giving the people what they want, here's a brief summary of what went on (You'll notice that I'm not giving names or locations of any of the work we did; we were at two sites, both of which are publicly owned, and since illegal collection on federal land is a recurring problem in eastern Oregon, I don't want to provide any information that an unscrupulous fossil poacher might be able to use; for those of you who are wondering, yes, we did have the appropriate permits).30 June 2010

Fossil Vertebrate of the Month: Bradysaurus

In honor of this year's World Cup host, July's fossil vertebrate is South African. Bradysaurus (literally "Slow Lizard," represented here by a skeleton from Berlin's Museum für Naturkunde) was a pareiasaur, a group of large, armored herbivores that may be distantly related to turtles. Though pareiasaurs have been found in late Permian sites throughout the Old World, Bradysaurus is unique to the Karoo Basin north and east of Cape Town. While pareiasaurs were among the largest members of the South African ecosystem, the fauna was dominated by therapsids, or "mammal-like reptiles," including the now-iconic, predatory gorgonopsians and burrowing dicynodonts. The Karoo has been the focus of many research projects in recent years because it is one of the few regions with a terrestrial fossil record of the Permian Extinction, the largest mass extinction in the history of life. Pareiasaurs were among the groups that would not survive the end of the Permian; if you want to see one today, I recommend Oregon's very own Prehistoric Gardens.

In honor of this year's World Cup host, July's fossil vertebrate is South African. Bradysaurus (literally "Slow Lizard," represented here by a skeleton from Berlin's Museum für Naturkunde) was a pareiasaur, a group of large, armored herbivores that may be distantly related to turtles. Though pareiasaurs have been found in late Permian sites throughout the Old World, Bradysaurus is unique to the Karoo Basin north and east of Cape Town. While pareiasaurs were among the largest members of the South African ecosystem, the fauna was dominated by therapsids, or "mammal-like reptiles," including the now-iconic, predatory gorgonopsians and burrowing dicynodonts. The Karoo has been the focus of many research projects in recent years because it is one of the few regions with a terrestrial fossil record of the Permian Extinction, the largest mass extinction in the history of life. Pareiasaurs were among the groups that would not survive the end of the Permian; if you want to see one today, I recommend Oregon's very own Prehistoric Gardens.

30 April 2010

Fossil Vertebrate of the Month: Platanistoid Dolphin

Modern dolphins are by many measures the most successful group of cetaceans: they are diverse, intelligent, and in many cases have proven more resistant to anthropogenic change than their larger relatives. Some dolphins have even colonized freshwater environments. These 'river dolphins' are often referred to as platanistoids, a name based on the modern genus Platanista that inhabits the Ganges and Indus Rivers (other genera inhabit the Amazon, La Plata, and - until recently - Yangtze Rivers), but there has been much debate about whether or not all river dolphins are actually related, as was originally thought. If the world's living and extinct river dolphins really are the product of separate colonizations of freshwater habitats, then they represent a striking example of convergent evolution: platanistoids share many morphological characteristics, perhaps the most striking being a long, pointed rostrum (or snout; this feature makes them similar in form to many other fish-eating vertebrates, such as ichthyosaurs and swordfish). The specimen at left, an as-yet unnamed platanistoid from the mid-Miocene of Oregon, exhibits this characteristic rostrum. However, it was uncovered from the Astoria Formation, a marine unit from the Oregon Coast, making it a saltwater freshwater dolphin. This implies that at least one lineage of river dolphins evolved its unusual morphology before migrating inland. To see this specimen, drop by the U of O's Museum of Natural & Cultural History's Paleolab exhibit, where it will be on display until this summer; if you're in Seattle, some very nice skulls of the similar (but unrelated) Eurhinodelphis are on display at the Burke Museum's Cruisin' the Fossil Freeway exhibit until the end of May.

Modern dolphins are by many measures the most successful group of cetaceans: they are diverse, intelligent, and in many cases have proven more resistant to anthropogenic change than their larger relatives. Some dolphins have even colonized freshwater environments. These 'river dolphins' are often referred to as platanistoids, a name based on the modern genus Platanista that inhabits the Ganges and Indus Rivers (other genera inhabit the Amazon, La Plata, and - until recently - Yangtze Rivers), but there has been much debate about whether or not all river dolphins are actually related, as was originally thought. If the world's living and extinct river dolphins really are the product of separate colonizations of freshwater habitats, then they represent a striking example of convergent evolution: platanistoids share many morphological characteristics, perhaps the most striking being a long, pointed rostrum (or snout; this feature makes them similar in form to many other fish-eating vertebrates, such as ichthyosaurs and swordfish). The specimen at left, an as-yet unnamed platanistoid from the mid-Miocene of Oregon, exhibits this characteristic rostrum. However, it was uncovered from the Astoria Formation, a marine unit from the Oregon Coast, making it a saltwater freshwater dolphin. This implies that at least one lineage of river dolphins evolved its unusual morphology before migrating inland. To see this specimen, drop by the U of O's Museum of Natural & Cultural History's Paleolab exhibit, where it will be on display until this summer; if you're in Seattle, some very nice skulls of the similar (but unrelated) Eurhinodelphis are on display at the Burke Museum's Cruisin' the Fossil Freeway exhibit until the end of May.

27 March 2010

Exhibit Review: San Diego Natural History Museum

This exhibit isn't new per se, but it is new to me and it's recent enough that I feel justified in reviewing it. Part of my impression of the San Diego museum may be colored by my time doing research in the collections, and it's worth noting that the facilities there are excellent, from the well-appointed prep lab to the well-organized cabinets of fossils to the offices with views over Balboa Park. That said, the exhibits there are among the best I've seen anywhere. The focus of Fossil Mysteries is deceptively constrained, displaying only fossils from the San Diego area. This is the sort of seemingly narrow focus that could lead to an exhibit consisting primarily of fossils on shelves: interesting, perhaps, to scientists, but with little value for anyone else. However, when put in the correct context, local fossils from sites familiar to museumgoers can be used as springboards to present broader concepts, and Fossil Mysteries does this to great effect. As the name of the exhibit suggests, this is done by presenting visitors with a series of questions. Some of these are rhetorical and answered fairly quickly (e.g. 'How can you tell different groups of carnivorous mammals apart?). Others (e.g. 'Why are there no more mammoths in Southern California?') are intentionally left unanswered, though visitors are provided with evidence they can use to draw their own conclusions. Of course, relying on museumgoers to actually read all an exhibit's signage is a bad bet, and several interactive displays are in place to appeal to younger visitors (my favorite was a series of self-powered displays on animal locomotion, all of which fed into the larger theme of adaptation). Models of some of the more impressive fossils are much in evidence (some of which are half skeletal, half fleshed-out); the full-sized Carcharodon megalodon and a prowling Panthera atrox are particularly impressive. A walk-through diorama of an Eocene jungle serves as an introduction to paleoecology. Many of the displays are augmented by vibrant murals by William Stout, which, taken as a whole, constitute one of the more impressive paleoartistic undertakings since Rudolph Zallinger's Age of Reptiles mural at Yale. One of the only drawbacks to Fossil Mysteries is the placement of these murals directly behind specimens, making them difficult to see and detracting from their full effect.

This exhibit isn't new per se, but it is new to me and it's recent enough that I feel justified in reviewing it. Part of my impression of the San Diego museum may be colored by my time doing research in the collections, and it's worth noting that the facilities there are excellent, from the well-appointed prep lab to the well-organized cabinets of fossils to the offices with views over Balboa Park. That said, the exhibits there are among the best I've seen anywhere. The focus of Fossil Mysteries is deceptively constrained, displaying only fossils from the San Diego area. This is the sort of seemingly narrow focus that could lead to an exhibit consisting primarily of fossils on shelves: interesting, perhaps, to scientists, but with little value for anyone else. However, when put in the correct context, local fossils from sites familiar to museumgoers can be used as springboards to present broader concepts, and Fossil Mysteries does this to great effect. As the name of the exhibit suggests, this is done by presenting visitors with a series of questions. Some of these are rhetorical and answered fairly quickly (e.g. 'How can you tell different groups of carnivorous mammals apart?). Others (e.g. 'Why are there no more mammoths in Southern California?') are intentionally left unanswered, though visitors are provided with evidence they can use to draw their own conclusions. Of course, relying on museumgoers to actually read all an exhibit's signage is a bad bet, and several interactive displays are in place to appeal to younger visitors (my favorite was a series of self-powered displays on animal locomotion, all of which fed into the larger theme of adaptation). Models of some of the more impressive fossils are much in evidence (some of which are half skeletal, half fleshed-out); the full-sized Carcharodon megalodon and a prowling Panthera atrox are particularly impressive. A walk-through diorama of an Eocene jungle serves as an introduction to paleoecology. Many of the displays are augmented by vibrant murals by William Stout, which, taken as a whole, constitute one of the more impressive paleoartistic undertakings since Rudolph Zallinger's Age of Reptiles mural at Yale. One of the only drawbacks to Fossil Mysteries is the placement of these murals directly behind specimens, making them difficult to see and detracting from their full effect.24 March 2010

Notes From a Golden Age

Apologies for the text color issues with this post; Blogger is either acting up today or I'm being an idiot. Either way, as an unredeemable perfectionist, I find it even more annoying than you do.

Apologies for the text color issues with this post; Blogger is either acting up today or I'm being an idiot. Either way, as an unredeemable perfectionist, I find it even more annoying than you do.

13 February 2010

Fossil Vertebrate of the Month: Cophocetus

This month's fossil vertebrate - and those for all the months between February and May - is a whale. This cetacean theme is in honor of the UO Museum of Natural and Cultural History's current exhibit, Whales of Deep Time. It's the first part of the three-part exhibit Paleolab-Oregon's Past Revealed (tune in this summer to find out about Part 2). This is, to a certain extent, shameless self-promotion, as I played a small part in putting the show together (I wrote some of the labels; drop by to see if you can guess which ones!). It's also the first time in decades that we've been able to put so many of the UO's more spectacular fossils on display, so if you have any interest in Northwest paleontology, it's well worth a visit.

This month's fossil vertebrate - and those for all the months between February and May - is a whale. This cetacean theme is in honor of the UO Museum of Natural and Cultural History's current exhibit, Whales of Deep Time. It's the first part of the three-part exhibit Paleolab-Oregon's Past Revealed (tune in this summer to find out about Part 2). This is, to a certain extent, shameless self-promotion, as I played a small part in putting the show together (I wrote some of the labels; drop by to see if you can guess which ones!). It's also the first time in decades that we've been able to put so many of the UO's more spectacular fossils on display, so if you have any interest in Northwest paleontology, it's well worth a visit.29 December 2009

2009: The Year In...

21 November 2009

Fossil Vertebrate of the Month: Tiktaalik

This November 24th marks the 150th anniversary of the publication of Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species, one of the most important books in history. Darwin famously devoted a chapter of his magnum opus to the imperfection of the fossil record and why transitional fossils supporting his theory might prove to be difficult to find. "Missing links" do remain rare, but they are uncovered from time to time, and the most spectacular example from recent history is this month's featured animal. Famously touted for its combination of fish and tetrapod features, Tiktaalik is actually a link in a well-documented transition between lobe-finned fish such as Eusthenopteron through "fishapods" such as Panderichthys and Acanthostega to true tetrapods such as Ichthyostega. Not only is Tiktaalik an impressive fossil (or, more accurately, group of fossils, as severals pecimens have been uncovered), but it provides an excellent example of the predictive power of evolutionary theory. Chicago paleontologist Neil Shubin actually went out looking for something very like Tiktaalik; he knew the approximate age of a gap in the tetrapod fossil record, he knew that most early tetrapod fossils had been found in rocks from around the edges of the North Atlantic, and that rocks of the appropriate age (Late Devonian) outcropped on Ellesmere Island in the Candian Arctic (one of the closest major land masses to the North Pole, appropriately enough for this time of year). Shubin's hypothesis proved to be correct, and a 2004 expedition uncovered the first remains of Tiktaalik, which has since taken its place alongside Archaeopteryx and Australopithecus as one of the most impressive transitional fossils ever discovered.

14 November 2009

Burian & Knight Videos

10 November 2009

New Look

09 September 2009

In the Wake of the Vikings

For the first time in more than two years, I have the distinct pleasure of updating this blog from Europe. My purpose for being here is twofold: at the moment I'm on a family vacation to Copenhagen and Ireland, at the end of which I'll be hopping across the Irish Sea to my old home in Bristol for the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meeting. My perhaps too-colorful title may make it sound like more of an adventure than it really is (though it is, strictly speaking, accurate, as Ireland and England were colonized by the Norse - and in particular by Danes - during the Middle Ages), but it is one of the bigger trips I've taken in my life, and I will do my best to file periodic travelogues (though now that I think about, a large percentage of my reading audience are either on this trip with me or will be rendezvousing with me in Bristol). I will also post photos to my Picasa account for any of you who might be interested in what, say, Roskilde looks like this time of year.

For the first time in more than two years, I have the distinct pleasure of updating this blog from Europe. My purpose for being here is twofold: at the moment I'm on a family vacation to Copenhagen and Ireland, at the end of which I'll be hopping across the Irish Sea to my old home in Bristol for the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meeting. My perhaps too-colorful title may make it sound like more of an adventure than it really is (though it is, strictly speaking, accurate, as Ireland and England were colonized by the Norse - and in particular by Danes - during the Middle Ages), but it is one of the bigger trips I've taken in my life, and I will do my best to file periodic travelogues (though now that I think about, a large percentage of my reading audience are either on this trip with me or will be rendezvousing with me in Bristol). I will also post photos to my Picasa account for any of you who might be interested in what, say, Roskilde looks like this time of year.