Artist: Jay Matternes

Year: 1969

One of the big milestones in paleontology this year was the reopening of the Smithsonian's fossil halls. It goes without saying that the National Museum of Natural History is one of the most visited and most influential paleontology museums in the world, and a big reason for its popularity and impact are the murals of Jay Matternes depicting different regions of the US through time. Matternes' murals of Cenozoic landscapes are particularly impactful, inspiring a generation of paleoartists and setting the gold standard for depictions of extinct mammals. From a scientific standpoint, these murals have aged extremely well (which, as we've seen is not always the case with paleoart; I was actually a bit shocked to learn that these were painted in the '60s, as they seem much more modern that that) and still routinely find their way into lecture slides and presentations of those of us that study mammal paleontology. Another reason for this is that they're gorgeous, as perhaps best exemplified by his reconstruction of the landscape of Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument in Idaho. If you've ever spent a summer evening along one of the West's riparian oases, this mural feels immediately familiar (give or take a ground sloth and mastodon or two). I love the play of shadow on the trees and water lilies and how the greenery contrasts with the bare hillsides in the background. The imminent demise of a beaver at the paws of a saber-toothed cat notwithstanding, it conveys the feeling of a calm evening along a three-and-a-half million year riverbank spectacularly well, making it a great testament to Matternes' skill.

Want to see more? From what I understand, Matternes' murals were too fragile to make it into the new exhibits, which is a shame (though I understand the Smithsonian did install recreations of some of them). Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument has a large-scale reproduction of this particular mural, and for reasons that are still not 100% clear to me, his famous depiction of Wyoming in the Eocene seems to have made its way to the New Mexico Museum of Natural History & Science. If you're not up for traveling to DC, Idaho, or Albuquerque, a new book on Matternes' work has just been published, and you can see some of his most famous works in an article just published in Smithsonian Magazine.

21 December 2019

20 December 2019

20 - Saber-toothed Salmon

Artist: Ray Troll (also pictured: a sculpture by Gary Staab)

Year: 2014

There is nothing more emblematic of the Northwest than salmon, and appropriately our fossil record is rich in these fish (including the oldest known member of the family). The most impressive of these has been known by several names: the saber-toothed salmon, the spike-toothed salmon (the second of these being more appropriate given that its enlarged canines were more tusk- than saber-like), Smilodonichthys, and Onchorhynchus rastrosus (this last, correct name reflecting the fact that it's more closely related to sockeye salmon than sockeye are to any other species). Regardless of what you call it, it was an impressively enormous animal, and no one has devoted as much canvas to it as Ray Troll. The species was originally decsribed from a site near Madras, Oregon, and the best-preserved specimens are still found in the area, so it was only appropriate that when the University of Oregon opened their new fossil hall in 2014 that O. rastrosus should be the centerpiece, and the collaboration between Troll and Staab resulted in the best tribute out there to this most magnificent of fish.

Want to see more? The UO Museum of Natural & Cultural History is well worth a visit for several reasons, this mural and sculpture chief among them (and I'm not at all biased because I spent so many hours working for and in the museum as a grad student).

Year: 2014

There is nothing more emblematic of the Northwest than salmon, and appropriately our fossil record is rich in these fish (including the oldest known member of the family). The most impressive of these has been known by several names: the saber-toothed salmon, the spike-toothed salmon (the second of these being more appropriate given that its enlarged canines were more tusk- than saber-like), Smilodonichthys, and Onchorhynchus rastrosus (this last, correct name reflecting the fact that it's more closely related to sockeye salmon than sockeye are to any other species). Regardless of what you call it, it was an impressively enormous animal, and no one has devoted as much canvas to it as Ray Troll. The species was originally decsribed from a site near Madras, Oregon, and the best-preserved specimens are still found in the area, so it was only appropriate that when the University of Oregon opened their new fossil hall in 2014 that O. rastrosus should be the centerpiece, and the collaboration between Troll and Staab resulted in the best tribute out there to this most magnificent of fish.

Want to see more? The UO Museum of Natural & Cultural History is well worth a visit for several reasons, this mural and sculpture chief among them (and I'm not at all biased because I spent so many hours working for and in the museum as a grad student).

17 December 2019

12-19 - John Day Fossil Beds Murals

Artists: Larry Felder & Roger Witter

Year: 2005

I'm getting us most of the rest of the way to Christmas by including several of the most gorgeous paleoart murals ever painted as a single item. In my defense a) it's the week after Finals Week at Gonzaga, so I've been doing nonstop grading for several days and b) these were all created as part of a single project. As such, they hearken back to one of paleontology's grandest traditions. Back before digital, "augmented reality" exhibits (and, before them, animatronic dinosaurs) one of the ways that museums were able to put flesh on the fossilized bones on display in their halls was to commission a paleoartist to paint a series of murals to display on the walls above the skeletons. We've seen a lot of Rudolph Zallinger in this series, who was part of this tradition, and probably the greatest series of paleoart murals ever painted was Charles R. Knight's project for Chicago's Field Museum. Sadly, museums-spomsored mural projects are less in evidence these days, but there are some spectacular exceptions, among them the San Diego Natural History Museum and John Day Fossil Beds National Monument. Both are, collectively, among the greatest works of contemporary paleoart, but the John Day murals are especially spectacular. I'm not sure there's any other item on this list that rewards close inspection quite so much. I've visited the Thomas Condon Paleontology Center at John Day many times, and on each visit, I've been surprised by new things (the insect on the vine in the image above, for example, I'd never noticed before a visit this summer). The background of these murals is much more than a backdrop; besides depicting the flora and fauna of ancient central Oregon represented by the fossils on display nearby, they are full of details that most visitors probably breeze right by. My favorite is the enigmatic carnivore Allocyon shown as a partially decomposed carcass in the far background of the largest mural (conveniently allowing the artist to not commit to exactly what group it belongs to), but every mural in the series is packed with such gems, be they North America's last non-human primate (Ekgmowechashala, Lakota for "Little Cat Man) nestled among the branches of a tree or early dogs hunting burrowing rodents on the grasslands of the Miocene. However, the most remarkable thing about the murals is not a subtle detail, but rather such a major feature that it's easy to overlook. Just as Zallinger used seasons to illustrate climatic and environmental change through the Cenozoic, the John Day murals use the time of day. The murals depicting the Eocene are set at sunrise, and as you move on through the Oligocene and Miocene, the angle of the sun changes, culminating in the late Miocene Rattlesnake Formation in the early evening. You have to want to get there, but if you want to see a work of art that, more than any other produced in the last 20 years, really makes you feel immersed in the ancient world while at the same time visually summarizing the pioneering work on paleoecology that's been done in the area, start planning a trip to central Oregon today!

Want to see more? John Day Fossil Beds National Monument is worth a trip for the murals alone, but the Condon Paleontology Center is, as I've had cause to assert several times, one of the best site-specific museums anywhere in the world. The scenery of central Oregon is also jaw-dropping, so, seriously, start planning that trip today!

Year: 2005

I'm getting us most of the rest of the way to Christmas by including several of the most gorgeous paleoart murals ever painted as a single item. In my defense a) it's the week after Finals Week at Gonzaga, so I've been doing nonstop grading for several days and b) these were all created as part of a single project. As such, they hearken back to one of paleontology's grandest traditions. Back before digital, "augmented reality" exhibits (and, before them, animatronic dinosaurs) one of the ways that museums were able to put flesh on the fossilized bones on display in their halls was to commission a paleoartist to paint a series of murals to display on the walls above the skeletons. We've seen a lot of Rudolph Zallinger in this series, who was part of this tradition, and probably the greatest series of paleoart murals ever painted was Charles R. Knight's project for Chicago's Field Museum. Sadly, museums-spomsored mural projects are less in evidence these days, but there are some spectacular exceptions, among them the San Diego Natural History Museum and John Day Fossil Beds National Monument. Both are, collectively, among the greatest works of contemporary paleoart, but the John Day murals are especially spectacular. I'm not sure there's any other item on this list that rewards close inspection quite so much. I've visited the Thomas Condon Paleontology Center at John Day many times, and on each visit, I've been surprised by new things (the insect on the vine in the image above, for example, I'd never noticed before a visit this summer). The background of these murals is much more than a backdrop; besides depicting the flora and fauna of ancient central Oregon represented by the fossils on display nearby, they are full of details that most visitors probably breeze right by. My favorite is the enigmatic carnivore Allocyon shown as a partially decomposed carcass in the far background of the largest mural (conveniently allowing the artist to not commit to exactly what group it belongs to), but every mural in the series is packed with such gems, be they North America's last non-human primate (Ekgmowechashala, Lakota for "Little Cat Man) nestled among the branches of a tree or early dogs hunting burrowing rodents on the grasslands of the Miocene. However, the most remarkable thing about the murals is not a subtle detail, but rather such a major feature that it's easy to overlook. Just as Zallinger used seasons to illustrate climatic and environmental change through the Cenozoic, the John Day murals use the time of day. The murals depicting the Eocene are set at sunrise, and as you move on through the Oligocene and Miocene, the angle of the sun changes, culminating in the late Miocene Rattlesnake Formation in the early evening. You have to want to get there, but if you want to see a work of art that, more than any other produced in the last 20 years, really makes you feel immersed in the ancient world while at the same time visually summarizing the pioneering work on paleoecology that's been done in the area, start planning a trip to central Oregon today!

Want to see more? John Day Fossil Beds National Monument is worth a trip for the murals alone, but the Condon Paleontology Center is, as I've had cause to assert several times, one of the best site-specific museums anywhere in the world. The scenery of central Oregon is also jaw-dropping, so, seriously, start planning that trip today!

11 December 2019

11 - The Road to Homo sapiens

Artist: Rudolph Zallinger

Year: 1965

You'd think the gigantic mural that is easily the most monumental reconstruction of ancient life and that revived the fresco secco style would be the most influential work by its artist, but The Road to Homo sapiens (more widely known as The March of Progress) surpasses it by far. In fact, while it may be impossible to quantify such things, it is almost certainly the most influential work of paleoart ever produced; it's certainly the most reproduced and parodied. Zallinger's intent, as described by the author of the book in which it was published, was to distill the complex story of human evolution as it was then understood into an easily understandable image. In a sense, it was a phenomenal success, as it very clearly conveys the connections and similarities between modern humans and our extinct relatives. Unfortunately, while it conveyed the connection of our species to our hominid relatives better than anyone could have predicted, it was not so effective at illustrating the complexity of the evolution of apes. Our particular corner of the primate evolutionary tree is a complex one, with numerous branches arising in the past, but with only one surviving today. Instead of glorious complexity, The Road to Homo sapiens seems to imply that human evolution was a straight line from Pliopithecus to our species. There's good reason to believe that Zallinger himself did not hold this view, but his work is often taken to imply that evolution is a linear progression towards a "more evolved" goal (in this case, us). The image is frequently used to lampoon evolutionary theory, a fact that no doubt has Zallinger spinning in his grave. It is also true, though, that the very fact anti-evolution groups set it up as a straw man is a testament to just how clearly the image depicts the concept of evolution. So, next time you see The Road to Homo sapiens doctored for a t-shirt or an advertising campaign, between eye rolls spare a thought for the Seattle-born artist that created the single most indelible image of biology's unifying theory.

Want to see more? The image was originally published in Early Man in the Life Nature Library, but if you want to get a taste of the myriad reproductions Zallinger spawned, just do a Google image search for "evolution."

Year: 1965

You'd think the gigantic mural that is easily the most monumental reconstruction of ancient life and that revived the fresco secco style would be the most influential work by its artist, but The Road to Homo sapiens (more widely known as The March of Progress) surpasses it by far. In fact, while it may be impossible to quantify such things, it is almost certainly the most influential work of paleoart ever produced; it's certainly the most reproduced and parodied. Zallinger's intent, as described by the author of the book in which it was published, was to distill the complex story of human evolution as it was then understood into an easily understandable image. In a sense, it was a phenomenal success, as it very clearly conveys the connections and similarities between modern humans and our extinct relatives. Unfortunately, while it conveyed the connection of our species to our hominid relatives better than anyone could have predicted, it was not so effective at illustrating the complexity of the evolution of apes. Our particular corner of the primate evolutionary tree is a complex one, with numerous branches arising in the past, but with only one surviving today. Instead of glorious complexity, The Road to Homo sapiens seems to imply that human evolution was a straight line from Pliopithecus to our species. There's good reason to believe that Zallinger himself did not hold this view, but his work is often taken to imply that evolution is a linear progression towards a "more evolved" goal (in this case, us). The image is frequently used to lampoon evolutionary theory, a fact that no doubt has Zallinger spinning in his grave. It is also true, though, that the very fact anti-evolution groups set it up as a straw man is a testament to just how clearly the image depicts the concept of evolution. So, next time you see The Road to Homo sapiens doctored for a t-shirt or an advertising campaign, between eye rolls spare a thought for the Seattle-born artist that created the single most indelible image of biology's unifying theory.

Want to see more? The image was originally published in Early Man in the Life Nature Library, but if you want to get a taste of the myriad reproductions Zallinger spawned, just do a Google image search for "evolution."

10 December 2019

10 - Nesting

Artist: Wesley Wehr

Year: 1978

Today's item is a bit of a change of pace. Nesting is not a depiction of the ancient world, but rather a drawing by a prominent Northwest artist who was inspired by the region's fossil record. Wes Wehr was a member of the somewhat loose-knit Northwest School of artists, whose most famous members were Morris Graves and Mark Tobey. Unlike many of his peers, Wehr was known for his small landscapes and his imaginary figures or "monster drawings." These latter drawings are wonderfully complex and absorbing, but they become perhaps a bit less enigmatic if you know much about Wehr's biography and the fossil record of the Okanogan Highlands of Washington and BC. Several sites on both sides of the border preserve a rich Eocene flora and fauna, and if you've ever seen the dark compressions of insects, flowers, pine needles, and leaves on the light-colored rocks of the Stonerose site in Republic, WA, you can't help but see those same forms in Wehr's drawings (the feathery "wings" on the figure above are dead ringers for Metasequoia, the dawn redwood so abundant at Stonerose). This is not simply idle speculation on my part, as Wehr himself was an amateur paleontologist who played a huge role in discovering and describing the fossils of Stonerose. His name is forever connected to the site, as a new genus of plant from Republic was named Wehrwolfia in honor of Wehr and his colleague, the paleobotanist Jack Wolfe. Given his connections to one of the Northwest's most important lagerstätten and his membership in the region's most significant visual arts movement, Wehr is proof that not only are science and art not mutually exclusive pursuits, but that each excels when incorporating the other.

Want to see more? Wehr's work is featured in museums throughout the Northwest; the image above is from the Northwest Museum of Arts & Culture in Spokane. If you're interested in Wehr's story, both Jack Nisbet and Kirk Johnson have included sections on him in recent books.

Year: 1978

Today's item is a bit of a change of pace. Nesting is not a depiction of the ancient world, but rather a drawing by a prominent Northwest artist who was inspired by the region's fossil record. Wes Wehr was a member of the somewhat loose-knit Northwest School of artists, whose most famous members were Morris Graves and Mark Tobey. Unlike many of his peers, Wehr was known for his small landscapes and his imaginary figures or "monster drawings." These latter drawings are wonderfully complex and absorbing, but they become perhaps a bit less enigmatic if you know much about Wehr's biography and the fossil record of the Okanogan Highlands of Washington and BC. Several sites on both sides of the border preserve a rich Eocene flora and fauna, and if you've ever seen the dark compressions of insects, flowers, pine needles, and leaves on the light-colored rocks of the Stonerose site in Republic, WA, you can't help but see those same forms in Wehr's drawings (the feathery "wings" on the figure above are dead ringers for Metasequoia, the dawn redwood so abundant at Stonerose). This is not simply idle speculation on my part, as Wehr himself was an amateur paleontologist who played a huge role in discovering and describing the fossils of Stonerose. His name is forever connected to the site, as a new genus of plant from Republic was named Wehrwolfia in honor of Wehr and his colleague, the paleobotanist Jack Wolfe. Given his connections to one of the Northwest's most important lagerstätten and his membership in the region's most significant visual arts movement, Wehr is proof that not only are science and art not mutually exclusive pursuits, but that each excels when incorporating the other.

Want to see more? Wehr's work is featured in museums throughout the Northwest; the image above is from the Northwest Museum of Arts & Culture in Spokane. If you're interested in Wehr's story, both Jack Nisbet and Kirk Johnson have included sections on him in recent books.

09 December 2019

9 - Horses

Artist: Mark Hallett

Hallett may be responsible for one of the most graceful depictions of a dinosaur ever produced, but if people from the general public are familiar with his work, it's likely because of his "family portrait" illustrations commissioned for the children's nature magazine Zoobooks. Particularly recognizable are his dinosaur diversity figures from the Zoobooks of my youth, but he really hit his stride with his illustrations of mammal families. His rhinos, elephants, and in particular horses really jump off the page, in large part because he reconstructs them as active, living animals. Never was this more true than with his horses, which kick, buck, and gallop chaotically across the page (while forming a pleasingly symmetrical half-circle). These portraits are especially effective at driving home the simple paleontological truth that the modern diversity of any group is just the tip of the iceberg by eschewing the chronological "march through time" so often favored by illustrators (for the best and often most frustrating of these, stay tuned!). Instead, modern zebras and onagers occupy space right next to Eocene species barely recognizable as horses, making it clear just how much of horse diversity lies in the past and showing the enormous array of forms horses have evolved through time.

Want to see more? I learned today that Zoobooks is still being published (and by Ranger Rick, another childhood favorite of mine, no less!) and Hallett's illustrations have continued to appear in recent years.

Hallett may be responsible for one of the most graceful depictions of a dinosaur ever produced, but if people from the general public are familiar with his work, it's likely because of his "family portrait" illustrations commissioned for the children's nature magazine Zoobooks. Particularly recognizable are his dinosaur diversity figures from the Zoobooks of my youth, but he really hit his stride with his illustrations of mammal families. His rhinos, elephants, and in particular horses really jump off the page, in large part because he reconstructs them as active, living animals. Never was this more true than with his horses, which kick, buck, and gallop chaotically across the page (while forming a pleasingly symmetrical half-circle). These portraits are especially effective at driving home the simple paleontological truth that the modern diversity of any group is just the tip of the iceberg by eschewing the chronological "march through time" so often favored by illustrators (for the best and often most frustrating of these, stay tuned!). Instead, modern zebras and onagers occupy space right next to Eocene species barely recognizable as horses, making it clear just how much of horse diversity lies in the past and showing the enormous array of forms horses have evolved through time.

Want to see more? I learned today that Zoobooks is still being published (and by Ranger Rick, another childhood favorite of mine, no less!) and Hallett's illustrations have continued to appear in recent years.

08 December 2019

8 - The Age of Mammals

Artist: Rudolph Zallinger

Year: 1967

The Age of Mammals is Zallinger's other major, though lesser known, mural at Yale. Like The Age of Reptiles, it is a fresco secco, painted on plaster applied directly to a wall. Like its larger counterpart, this gives it an impressive clarity and makes its colors especially vibrant. Another similarity between the two pieces is the use of trees to demarcate geological epochs. It may lack the monumentality of The Age of Reptiles, but The Age of Mammals has in many ways aged far better. Not only do the subjects remain fairly accurate today (as opposed to the plodding, swamp-bound dinosaurs of Reptiles), but the mural is one of the best visual depictions of the changing climates and environments of the last 65 million years (I'd say it was the best bar none but for a series of works that will be showing up here shortly). Zallinger drives home the cooling a drying trends that have exemplified the Cenozoic in a really clever way. At the far left, in the Paleocene and Eocene, the landscape is lush and green with tropical plants; it is, for all intents and purposes, Spring. As you move right into the Oligocene and Miocene, trees start to give way to grasslands, and the color of the foliage and angle of the light makes it clear you've moved on into Summer. As extreme cooling starts to set in in the Pliocene, the leaves on the remaining trees have started to show their Autumn colors, and at the far right of the mural, in the Pleistocene, frost and snow-capped peaks signal the arrival of Winter and the Ice Ages. The causes and ecological effects of this large-scale climatic change are one of the major areas of study in paleontology today, and Zallinger gave these changes a (nearly) unequalled visual summary over 50 years ago.

Want to see more? As with most of Zallinger's work, The Age of Mammals is on view at the Peabody Museum until renovations begin at the end of the month.

Year: 1967

The Age of Mammals is Zallinger's other major, though lesser known, mural at Yale. Like The Age of Reptiles, it is a fresco secco, painted on plaster applied directly to a wall. Like its larger counterpart, this gives it an impressive clarity and makes its colors especially vibrant. Another similarity between the two pieces is the use of trees to demarcate geological epochs. It may lack the monumentality of The Age of Reptiles, but The Age of Mammals has in many ways aged far better. Not only do the subjects remain fairly accurate today (as opposed to the plodding, swamp-bound dinosaurs of Reptiles), but the mural is one of the best visual depictions of the changing climates and environments of the last 65 million years (I'd say it was the best bar none but for a series of works that will be showing up here shortly). Zallinger drives home the cooling a drying trends that have exemplified the Cenozoic in a really clever way. At the far left, in the Paleocene and Eocene, the landscape is lush and green with tropical plants; it is, for all intents and purposes, Spring. As you move right into the Oligocene and Miocene, trees start to give way to grasslands, and the color of the foliage and angle of the light makes it clear you've moved on into Summer. As extreme cooling starts to set in in the Pliocene, the leaves on the remaining trees have started to show their Autumn colors, and at the far right of the mural, in the Pleistocene, frost and snow-capped peaks signal the arrival of Winter and the Ice Ages. The causes and ecological effects of this large-scale climatic change are one of the major areas of study in paleontology today, and Zallinger gave these changes a (nearly) unequalled visual summary over 50 years ago.

Want to see more? As with most of Zallinger's work, The Age of Mammals is on view at the Peabody Museum until renovations begin at the end of the month.

06 December 2019

6 & 7 - Cretaceous Marine Life

|

| Reptiles Return to the Sea by Rudolph Zallinger, reproduced from The World We Live In |

Years: 1955 & 2018

One of Zallinger's lesser-known paintings occupies a much less prominent spot in Yale's fossil hall, but I've always had a soft spot for it. The clarity of its animals and the land-, sea-, and skyscapes they occupy are classic Zallinger and mirror the more monumental Age of Reptiles across the room. In this depiction of the continental sea that covered Cretaceous Kansas, though, there's more of a sense of movement, particularly in both the long- and short-necked plesiosaurs at the center. As with many works of paleoart, this scene is unnaturally crowded with animals, to better illustrate the diversity of the shallow seas. If you like crowded, vibrant reconstructions of past ecosystems, though, look no further than Ray Troll's illustration of another Cretaceous ocean, this one in what is now Vancouver Island. Plesiosaurs, mosasaurs, turtles, and a bewildering diversity of fish and cephalopods wend past and among one another, along with Troll's characteristic use of brilliant color imparting vitality to the 80-million-year-old seascape. Long-necked elasmosaurs occupy featured roles in both paintings, and the differences between them reflect our changing understanding of these bizarre marine reptiles. The Vancouver Island elasmosaurs are shown with stiff necks, not the serpentine, mobile necks depicted by Zallinger (and many other artists of his era). Also look at the flippers on the elasmosaur to the right of the Troll painting: its forward flippers are raised while its rear flippers are lowered, "flying" through the water in the way suggested by recent biomechanical research.

Want to see more? A version of Zallinger's painting is on display for another few weeks at Yale's Peabody Museum before its exhibits close for renovation. Troll's seascape, along with several others, is featured in his fantastic book with Kirk Johnson, Cruisin' the Fossil Coastline, and as always you can see an overview of his work at trollart.com.

.jpg?bwg=1543862610) |

| North Pacific Cretaceous Marine Life by Ray Troll |

05 December 2019

5 - Crossing the Flats

|

| Courtesy of Tetrapod Zoology |

Year: 1986

Dinosaurs won't figure too prominently on this list, in large part because the strength of the regional fossil record is post-Cretaceous. That said, Oregon is home to one of the most influential paleoartists of the so-called "Dinosaur Renaissance," and I would be remiss to not feature Mark Hallett's work here. The '70s through the early '90s were a heady time for dinosaur researchers, as new methodologies, new discoveries, and new ways of interpreting old fossils revolutionized our understanding of dinosaur biology. It was also a time when paleoart really blossomed, and Hallett in particular really shone during this era. This is my favorite of his dinosaur paintings, depicting not a fight to the death as Knight might have done or accentuating the monumentality of his subject to an almost supernatural degree as Zallinger did, but a quiet moment between a mother Mamenchisaurus and her offspring. As a Seattleite, I immediately appreciated that this scene seemed to be playing out between squalls on a fall day, and adding that touch of realism made the dinosaurs feel that much more real. This realism and the ability to depict prehistoric animals as just that, animals rather than monsters, is a hallmark of Hallett's work, and it's never been on clearer display than in Crossing the Flats.

Want to see more? This painting was prominently featured in the Natural History Museum of LA County's groundbreaking paleoart exhibition "Dinosaurs Past to Present" and is prominently featured in the exhibit catalog. I believe that the original is still owned by the LACM, but at least last time I was there it was not on display.

04 December 2019

4 - Helicoprion

Artist: Ray Troll & Memo Jauregi

Year: 2013

One of the best things to happen to paleontology, especially in this part of the world, in recent years is the addition of paleoart to Ketchikan-based artist Ray Troll's repertoire. This is far from the last of Troll's art that will make an appearance on this list, but I'd be remiss if I didn't include one of his many reconstructions of the whorl-toothed "shark" (actually more closely related to ratfish) Helicoprion. Despite being first described in Australia and brought to the attention of the wider scientific community by Russian scientists, Idaho has the most and the best fossils of this bizarre and enigmatic animal. It was at Idaho State University that the long-standing mystery of how exactly the spiral tooth row fit into the skull was solved, a study that also shed light on the relationships of this and other early shark relatives. In a testament to why collaborations between artists and scientists are so important, Troll himself played a major role in this process; it's a great story, but I'll save myself a lot of writing and refer you to Susan Ewing's Resurrecting the Shark which explores the Helicoprion saga from its inception to the present day.

Want to see more? The mural shown above is part of a traveling exhibit on Idaho's "buzzsaw" sharks that, last I heard of it, was on display at the Idaho Museum of Natural History. You can always view Ray Troll's work at his fantastic website if you can't make it to Pocatello (or wherever the exhibit it headed next).

Year: 2013

One of the best things to happen to paleontology, especially in this part of the world, in recent years is the addition of paleoart to Ketchikan-based artist Ray Troll's repertoire. This is far from the last of Troll's art that will make an appearance on this list, but I'd be remiss if I didn't include one of his many reconstructions of the whorl-toothed "shark" (actually more closely related to ratfish) Helicoprion. Despite being first described in Australia and brought to the attention of the wider scientific community by Russian scientists, Idaho has the most and the best fossils of this bizarre and enigmatic animal. It was at Idaho State University that the long-standing mystery of how exactly the spiral tooth row fit into the skull was solved, a study that also shed light on the relationships of this and other early shark relatives. In a testament to why collaborations between artists and scientists are so important, Troll himself played a major role in this process; it's a great story, but I'll save myself a lot of writing and refer you to Susan Ewing's Resurrecting the Shark which explores the Helicoprion saga from its inception to the present day.

Want to see more? The mural shown above is part of a traveling exhibit on Idaho's "buzzsaw" sharks that, last I heard of it, was on display at the Idaho Museum of Natural History. You can always view Ray Troll's work at his fantastic website if you can't make it to Pocatello (or wherever the exhibit it headed next).

03 December 2019

3 - The Age of Reptiles

|

| Courtesy of Sauropod Vertebra Picture of the Week |

Year: 1942-1947

Unsurprisingly, viewing paleoart is not usually akin to a religious experience; The Age of Reptiles in Yale's Peabody Museum is the one excepetion I know of, and it's a big one. This was an intentional choice on the part of artist (and Seattleite!) Rudolph Zallinger, who painted it as a fresco (that is, on a plaster base applied directly to a wall), a style generally associated with church decoration in the Middle Ages. The mural is easily the biggest and most influential work in this style since the Renaissance, and Zallinger completed it over several years while the museum was open, just as Medieval artisans added on to cathedrals in a piecemeal fashion. What truly makes the mural awe-inspiring, though, is its scope, as it covers over 350 million years of Earth history and 110 feet of the Peabody's Great Hall wall. There's a lot more to The Age of Reptiles than its enormous scale, though. Clarity, contrast, and attention to detail are hallmarks of Zallinger's work, and these are on full display in this masterpiece. As a fresco, the images on the mural remain as colorful and vibrant today as the day they were painted (all the more remarkable considering a color palette that is much more muted than in many works of paleoart). This, again along with their sheer size, gives so many of the animals here a truly monumental feel; the best examples are the wallowing Apatosaurus and lumbering Tyrannosaurus (supposedly the model for Godzilla). My favorite part of the mural, though, is that Zallinger takes advantage of its scale to prominently feature the landscape. I don't know that vegetation features as prominently in any other work of paleoart; not only has Zallinger clearly done his paleobotanical homework, but he uses full-sized trees as breaks between adjacent geological periods. The background is also suitably epic, particularly the soaring cliffs of the Permian and the menacing volcanoes of the Cretaceous. Scientifically speaking, depictions of many of the animals (especially the dinosaurs) have not aged well, but that does not detract one iota from the mural's status as one of the truly great works of paleoart; it would not, however, be Zallinger's most influential piece, for which you should stay tuned...

Want to see more? If you want to see this mural soon, you should get to Yale ASAP, as the Peabody Museum closes for renovations later this month. Don't despair if you can't make it on such short notice, though, as it looks like the planned renovation is going to make the mural even more visible and integral to the exhibit.

1 & 2 - Two Views of the Burgess Shale

It's the holiday season again, so I'm reviving one of my favorite traditions, the Paleontology Advent Calendar. This year I wanted to celebrate paleoart, the depiction of prehistoric worlds. Specifically, I wanted to highlight art by artists from the Northwest or art depicting the geological history of my favorite corner of the world. I'm a little behind the 8-ball this year, so I missed the first two days, but fortunately they work so well as a pair that I'm sharing them together now!

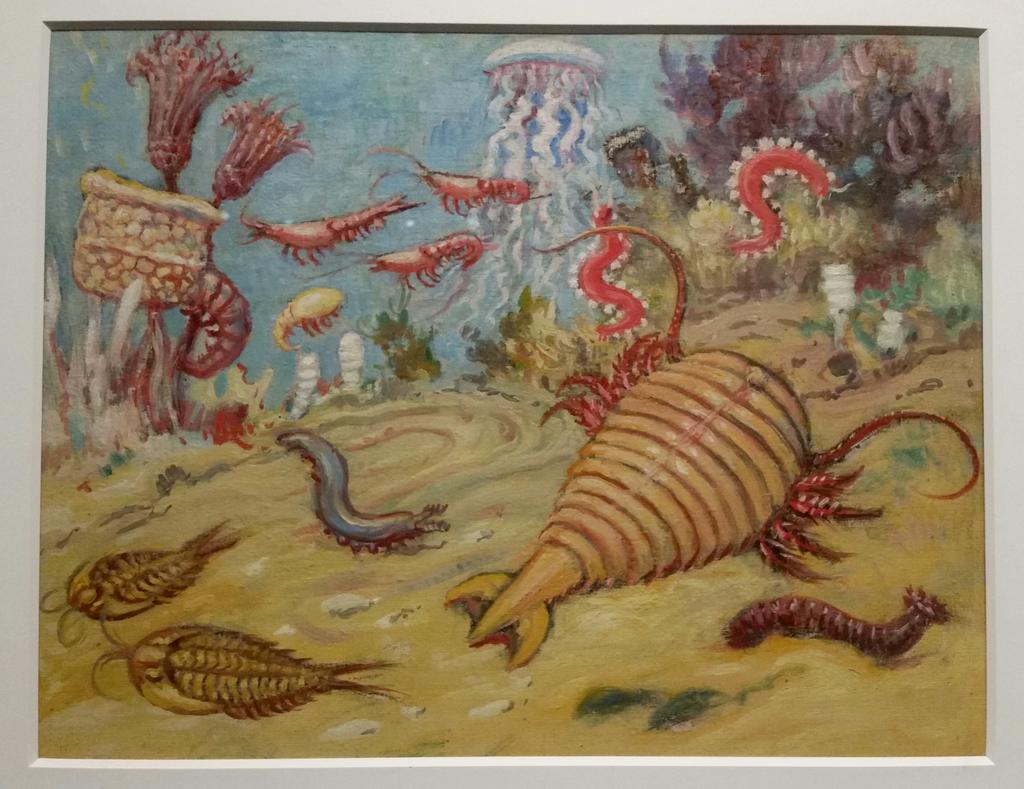

Artists: Charles R. Knight & Douglas HendersonYears: 1944-1946 & 2003

We begin with a bang with the most important fossil site in the Northwest, the Burgess Shale, and two titans of paleoartistry, Charles R. Knight and Douglas Henderson. Just why is the site so important and why do these two occupy such prominent places in the paleoart pantheon? As it happens, this pair of paintings answers both questions. Each illustrates what makes the artist's work so wonderful. In Knight's case, it's his generous use of color, his almost impressionist backgrounds, and his ability to convincingly depict movement (exemplified by the shrimp and worms at the center of this painting) that make his subjects leap off the canvas and seem so alive. The sunlight, shadow, and utterly immersive world of Henderson's painting illustrates his greatest strength: using pastels to create believable, engaging, and evocative environments in which the organisms themselves often take a back seat to atmosphere and setting. For my money, Henderson is the greatest of all paleo-landscape (or in this case, seascape) artists, and Knight is widely recognized as the preeminent painter of ancient animals. While Knight was frequently ahead of his time in his depictions of prehistoric life, here's one case where he got things wrong, depicting the fauna of the Burgess Shale as essentially identical to their distant descendants of the present day. Note in particular the strange, shrimp-like animal in the upper left and the jellyfish in the background. Strictly speaking, neither of these animals ever existed. Instead, as is often the case with the Burgess Shale, reality is far stranger and much more interesting. The large animal at the center of Henderson's painting is Anomalocaris, one of the first large predatory animals on Earth. It was so large, in fact, that early paleontologists studying the Burgess Shale found several bits and pieces of it but never considered that all these parts might fit together into a single organism; the "shrimp" in Knight's painting is an appendage from an Anomalocaris head and the "jellyfish" is its disc-like mouth. This diversity of forms, dating to nearly the beginning of animal life and inconceivable to the Gilded Age paleontologists who found and described the site, is what makes the Burgess Shale so incredible.

Want to see more? This is one of many Knight paintings on display at the Natural History Museum of LA County, but if you can't make it to California, there's an excellent online gallery of his work. Henderson also maintains a website on which you can not only view but buy much of his work (including the painting shown here).

15 April 2019

Heritage Matters

As a paleontologist, I've always felt a kinship with others who study the past: geologists, archaeologists, and historians of art, architecture, literature, and so many other areas of human achievement. Just as life and landscapes of the past illuminate the saga of our planet and help us better understand our changing world, studying humankind's heritage enriches our identity, warning us away from what we are capable of at our worst and inspiring us towards the transcendent acts of creativity and humanity we are capable of at our best. No one understands the value of heritage better than the French, whose word for it - patrimoine - reflects the view that the buildings, landscapes, works of art, and ideas developed by past generations are not only the legacies of their creators but collectively define who we are and what we can become. The concept of patrimoine carries with it a sense of duty to protect that inheritance and the recognition that the loss of heritage is not only a societal tragedy, but one that shakes the very foundations of that society. Knowing just how important patrimoine is to French culture and identity made it especially jarring to receive a news alert this morning that the greatest icon of French heritage was in danger, that Notre-Dame was burning.

I was lucky to be able to visit Notre-Dame de Paris early one morning on my visit to the city last summer and to have a conference commute that allowed me twice-daily views of its flying buttresses soaring above the Seine. Even if I hadn't had an appreciation for its importance to Paris, France, Europe, and the world, its status as a cultural cornerstone would have been impossible to miss. It is rooted in Gallo-Roman Lutetia, it blossomed in the Middle Ages, and it stands today in the heart of one of the world's great cities. Its history is inextricably linked with that of Paris and it stands as a shining example of patrimoine in a city and country with a unique appreciation of that concept. I can only imagine, then, the horror and sadness that Parisians must be feeling as they watch the images that have stunned us all across the globe and my heart goes out to everyone, including many of my own friends and family, with connections to the City of Lights. Even having only visited the cathedral once, the destruction wrought by the Notre-Dame fire leaves me with a deep sense of loss. It is a sadly familiar feeling, the same I felt last September when flames tore through Brazil's Museu Nacional. In both cases, fire caused significant damage to the building itself (though thankfully most recent reports seem to suggest that the firefighters of Paris were able to avert the near-total destruction of the Rio de Janeiro tragedy), but just as damaging was the loss of the many artifacts, specimens, and works of art contained within. The damage to Notre-Dame will undoubtedly be repaired and the destroyed portions will be rebuilt; like any of the great cathedrals, it already bears the marks of centuries of decay, destruction, repair, and growth and ultimately even today's catastrophic fire will amount to another chapter - not the final page - in its illustrious history. Regardless of whether you're French, European, or simply just human, though, a part of our collective inheritance was forever damaged today. The wound will heal, but the scar will remain.

Another similarity between last year's fire in Brazil and today's in Paris is that both were likely avoidable. In Rio de Janeiro, museum staff had long warned that the museum and its collections were vulnerable to damage from a fire. In Paris, repairs on vulnerable parts of the cathedral had just begun after a campaign for funding that took far longer than it should have had to. It is easy to take patrimoine for granted. Particularly in European culture, there is a tendency to view great monuments, works of art, and artifacts as permanent features on our cultural landscape. To truly appreciate our heritage, though, is to recognize that not only are we defined by it but that we are stewards of it and that without our care even the most significant of inheritances can be lost. In hopes that something positive can come out of disasters like the Notre-Dame and Museu Nacional fires, I have two requests for whoever reads this: regardless of where you live or what your background is, appreciate our shared heritage and advocate for it. Appreciation is the easy (and fun!) part. You may not live near Notre-Dame, the Pyramids of Giza, or the Taj Mahal, but somewhere near you a structure was built or a work created that has played a role in defining the human experience. Likewise, you probably live in or near a landscape or ecosystem that sheds light on the broader shared experience of Earth and life history (not all heritage is cultural, after all). Such sites are not hard to find. The gold standard of heritage directories is the World Heritage List maintained by Paris-based UNESCO (the United Nations Education, Scientific, and Cultural Organization; in other words, the arm of the UN that deals with the things that make life worth living). UNESCO also maintains lists of Biosphere Reserves and Creative Cities, but even if you don't live near a site of obvious international significance, individual countries and regions maintain their own heritage registries. In the US, I especially recommend the directories of the American Alliance of Museums and the Cultural Landscape Foundation as well as, of course, the National Park Service and the state park service of your home state. Regardless of where in the world you are, opportunities abound to explore our natural and cultural heritage, and I can safely guarantee that that doing so will be immensely rewarding.

Advocacy is more difficult, but it's immensely important. Dangers to our heritage are everywhere, as exemplified by today's fire in Paris and attested to by UNESCO's depressing List of World Heritage in Danger. In some cases violence and war take their toll (see that sad cases of destruction of historic sites in Mali and Syria), and in others the more prosaic forces of population growth, economics, and public policy have taken theirs (lest you think I'm referring only to "developing" countries, note that right here in the US proposed cuts to the Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monuments threaten not only an iconic landscape but the cultural heritage of the peoples of the Four Corners region). Environmental destruction and climate change threaten not only natural ecosystems but cultural sites such the Micronesian ruins of Nan Madol that may become submerged as sea levels rise. Being responsible stewards of our heritage is more important now than it ever has been, and there are many ways that any and all of us can contribute. You don't need to be a teacher to educate others about the importance of heritage; in the age of smart phones, most of us literally hold in our hands the means the means of learning about a natural area, historic site, or work of art and sharing that knowledge with the world. You don't need to be a great philanthropist to financially support heritage stewardship; many sites are run by nonprofit organizations that you can join as a member or help fund with even a small donation (reconstruction of Notre-Dame, for example, will be driven by an international fundraising campaign). You don't need to be a historian or naturalist to get directly involved; volunteers are nearly always welcome at any site of natural or cultural importance and in a connected world we can often make contributions from the other side of the planet (for example, by contributing photos to digitally archive the Museu Nacional). Finally, you don't need to be a politician or lobbyist to affect policy; public pressure and voting may ultimately be more effective at protecting our heritage than any legal action.

Like any site or object that is part of our collective patrimoine, Notre-Dame is not only a monument to our past but a testament to the creative genius of our species that, through luminaries such as Victor Hugo and the impressionists, has inspired new visions of what we can accomplish and what we can be. Inspiration and understanding are the most valuable gifts imparted to us by our natural and cultural heritage, but this inheritance from our ancestors and our planet comes with a charge of stewardship. As today's events show, when that stewardship lapses, tragedies can occur that affect us all.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)