04 December 2013

Fossil Vertebrate of the Month: Nimravus brachyops

As a paleoecologist, interactions between animals and their environments are my stock-in-trade. For the most part, paleoecologists study these interactions by observing trends through time in the variables of interest in search of macroscopic patterns. Every now and then, though, a fossil turns up that captures (or at least appears to capture) an interaction between an individual and some aspect of its environment (usually another animal). The most famous examples of this are, unsurprisingly, saurian: I had the opportunity to view the amazing Mongolian "Fighting Dinosaurs" when they were on display in New York a few years back, and another pair has made headlines for all the wrong reasons in recent weeks. However, no specimen provides as good an example of both the power and the pitfalls of "fighting fossils" as a skull in the University of Nebraska State Museum. It is a specimen of Nimravus brachyops, a member of the eponymous Nimravidae. Nimravids are a fascinating group of carnivores in their own right: they are mid-sized saber-toothed predators that were particularly abundant in the Oligocene and are nearly indistinguishable from cats but are probably closer relatives of civets. This specimen, however, is of interest from more than just a scientific point of view. It was found with a canine embedded in the humerus of another N. brachyops, showing that the two individuals had died fighting. That, at least, was the conclusion of the field crew that first uncovered the specimen. This crew included a young Loren Eiseley, who would go on to become one of the most prominent naturalists of the 20th Century. Eiseley was so impressed by the specimen that it inspired him to write one of his most famous poems, 'The Innocent Assassins.' The picture painted by the fossils and by the poem is certainly dramatic, but is it accurate? Paleontology has long been plagued by studies that put good stories in front of the evidence of the fossil record and, unfortunately, this may be one of them. First of all, there is no irrefutable evidence that more than one individual was present (in paleontological parlance, the Minimum Number of Individuals is 1, meaning that it is impossible to disprove that both bones came from the same animal). Of course, no one would suggest that the nimravid bit through its own arm. However, it is possible that the humerus and the canine were driven together after death, either during transport or, probably more likely, during burial. As others have observed, this latter scenario is supported by the fact that the canine, while broken towards its tip, is largely intact. One of the major paradoxes of saber-toothed predators is that elongated canines are, for the most part, exceptionally brittle and would have broken remarkably easily if too much stress were applied to them. It beggars belief that this Nimravus had canines robust enough to not only puncture bone but to remain mostly intact during the struggle that would have followed. Perhaps the Nebraska specimen really does represent a death struggle, but the balance of probability is that taphonomy, not paleoecology, provides the explanation for the association between the two bones. For those of you who find this depressingly banal, I hasten to add that this does not mean that nimravids never fought. A well-known specimen from South Dakota seems to represent a Nimravus skull that has been punctured by the saber of the smaller nimravid Eusmilus, and a talk at this year's Geological Society of America Meeting suggested that such injuries might be more common than previously thought. Nimravids may very well have been preternaturally pugnacious, but for all of Eiseley's eloquence, the true drama of the "Innocent Assassins" specimen lies not in the moment of death but in the evolutionary and ecological story into which the fossil fits.

13 November 2013

Fossil Vertebrate of the Month: Stegomastodon

|

| Holyoke Stegomastodon Tusk Denver Museum of Nature & Science |

Relevance to my family's history is not the only reason I'm featuring Stegomastodon this month. It was among the last of the gomphotheres, one of the most prolific (though probably paraphyletic) groups of proboscideans (despite what the name might suggest, it was neither a close relative of the North American mastodon nor of the Asian Stegodon). Elephants and their relatives are one of the great triumphs of mammal evolution, due in large part to their ability to disperse widely, and Stegomastodon represents an especially important milestone in this history: it was one of only two proboscidean genera to colonize South America during the American Biotic Interchange (the other being Cuvieronius, also a gomphothere). Instead of being just an isolated specimen from eastern Colorado, then, the Holyoke Stegomastodon was part of the last great success story of a once diverse group of proboscideans, a story that unfolded not just on the Great Plains, but across Panama and into the Pampas of South America.

07 November 2013

Regeneration

In the past few months, I've moved to Iowa, started my new job at Cornell College, and leaped headlong into the deep end of the block-system-teaching pool here. Having been caught up in these fairly major life changes, I allowed this blog to go fallow (though I did take the time to update the title and the appearance) and seriously considered shuttering it altogether. However, I spent the last week and a half in Denver and Los Angeles attending the annual meetings of the Geological Society of America and the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, which came at exactly the right time for me. They reminded me that the world of paleontology is an exciting one, and as I'll be arguing in a forthcoming post, it is a world in a greater state of flux than ever before. I can hardly claim to be the most articulate voice for paleontology out there, nor am I the type to write new posts daily, but I do think science blogs have real value (especially in an age where even scientific societies seem to prefer the vapid blurbs of Twitter). If I can be even a moderately effective medium between paleontology and the general public, then I'll feel I've done a good job. In the true spirit of my alma mater, then, it's time for the Mammoth Prairie to rise from the ashes of the Oregon Trail; whether or not I fulfill the Chicago motto by growing knowledge and enriching life will be for you all to judge.

04 July 2013

Fossil Vertebrate of the Month: Diceratherium

|

| Diceratherium John Day Fossil Beds National Monument |

01 June 2013

Fossil Vertebrate of the Month: Tylosaurus ivoensis

|

| Tylosaurus. ivoensis and other marine vertebrates from the Karlstad Basin (Sørensen et al 2013) |

31 May 2013

The Mammoth Prairie

|

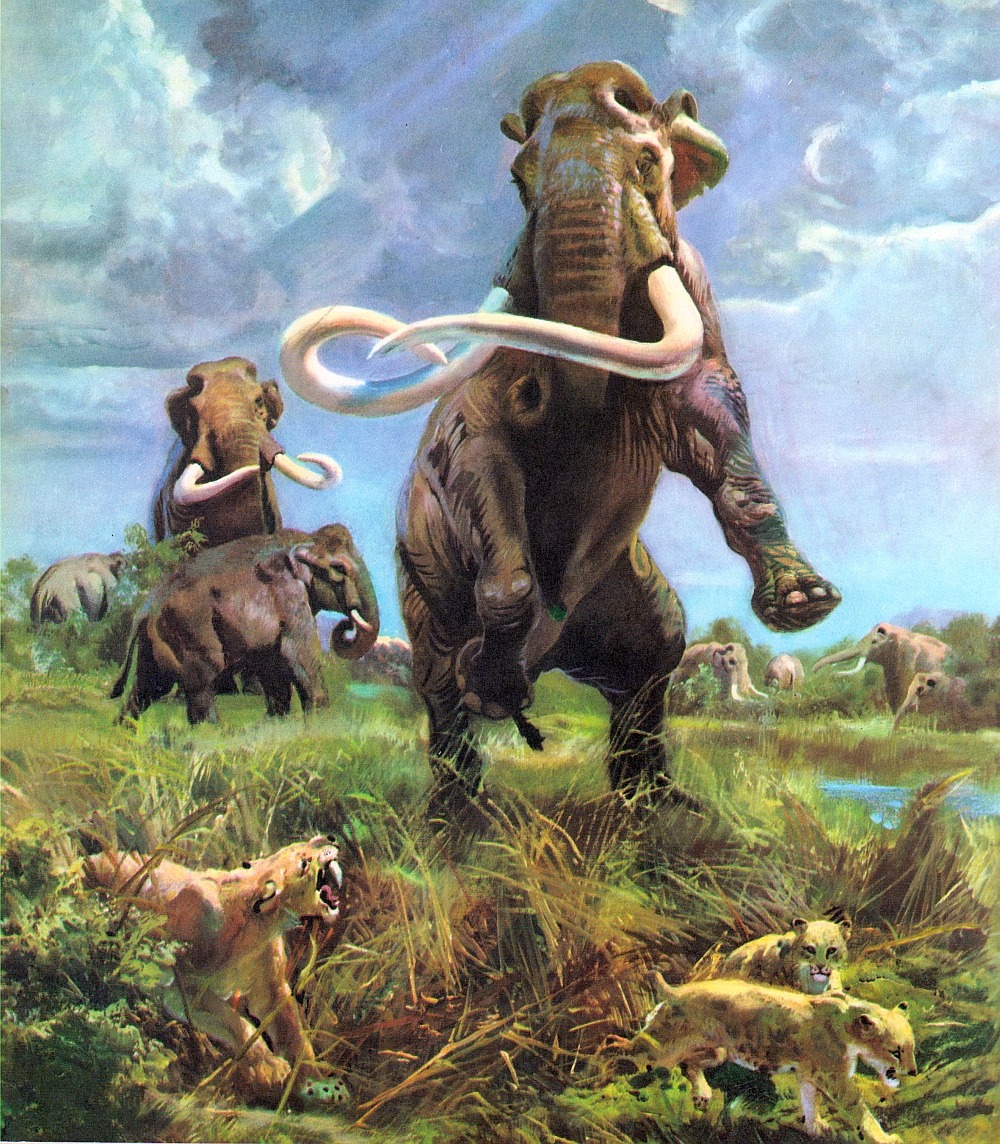

| Mammoths & Sabertooth Cats (Zdenek Burian) |

24 May 2013

Bellingham's Big Bird

|

| DiatrymaUniversity of Wyoming Geological Museum |

The western half of the Northwest is, for the most part, a geologically young landscape, shaped by the still-growing Cascades and by sediments deposited during the Pleistocene. The fossils found here are, for the most part, correspondingly young. In the Puget Sound Lowlands and the Willamette Valley in particular the vertebrate fossil record is dominated by Ice Age mammals (including the Manis Mastodon). However, there are pockets of older rocks in the region, including the Oligo-Miocene formations of the outer coast that have yielded some of the world's most important specimens of marine mammals and the marine reptile-bearing Cretaceous rocks along the Strait of Georgia. Among the most unusual vertebrate fossils in the region are those from the Chuckanut Formation near Bellingham. In the Eocene, the area was a low-lying floodplain in a warm climate (as indicated by the palm fronds that have been found there). Bones of fossil vertebrates are rare in the formation, but many animals left their footprints in the then-soft sediments of the floodplain, several of which have been preserved as fossil trackways. Trackways and other trace fossils are invaluable paleoecological tools, as they preserve direct evidence of interactions between organisms and their environment. A recent publication out of Western Washington University describing a pair of giant bird tracks from the Chuckanut Formation is a nice case study of the use of fossil footprints in making inferences about the behavior of extinct animals. One of the Eocene's most charismatic animals was the giant flightless bird Diatryma (possibly the same animal as the European Gastornis of BBC fame). Diatryma bones are well-known from the Eocene beds of Wyoming, and when it was first discovered by Edward Drinker Cope in the late 19th Century, it was thought to be a carnivore and was frequently depicted as preying upon the small horses that were common in the area. However, it has subsequently been hypothesized that Diatryma was herbivorous, possibly using its large beak to crack nuts or fruit rinds. The Washington tracks have been tentatively assigned to Diatryma or a close relative; while assigning trace fossils to a taxon previously known from body fossils always entails some risk, but since no other large birds are known from the Eocene of North America, in this case the authors are not going out on too much of a limb. If the tracks were indeed made by Diatryma, they provide some hints as to the animal's behavior, as they don't seem to show any evidence of the sharp talons that characterize modern predatory birds (including, significantly, the terrestrial secretary bird). This is not, of course, the final word in the debate; it's entirely possible that if Diatryma were a predator, it relied more on its beak than its feet for hunting, and it's not outside of the realm of possibility that evidence of talons simply wasn't preserved in these tracks. However, the footprints do provide a novel viewpoint, and it is certainly to be hoped that the Chuckanut Formation will continue to produce fossils that will help elucidate the ecology of Eocene ecosystems.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)